Tracing the colonial remnants along River Nile

Hey there!

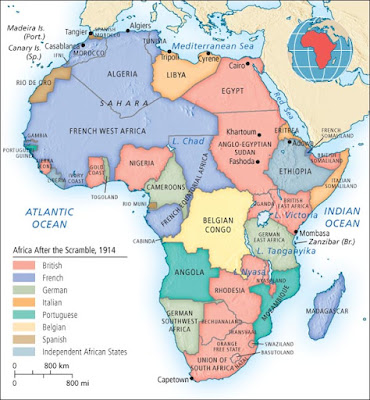

As I position the focus of my blogs on the transboundary conflicts within the Nile Basin, it is important to remind ourselves that these very boundaries were not established by Africans- they were created by European nations during the Scramble of Africa. A thorough understanding of the current conflicts would only be complete by investigating the historical context of the riparian states and how the dynamics of this piece of history from the early 20th century manifests itself into the present era. Under a post-colonial lens, we will delve into the trifold of industrialism, bilateral agreements, and unilateral actions attributed to the Nile Basin's transboundary conflicts.

Colonialism and Industrialism

European powers colonised the major riparian countries from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century: Britain controlled Egypt and Sudan, Italy dominated Eritrea and Ethiopia, and France and Belgium conquered Equatoria (Swain, 1997). These European powers did not only extract natural resources from the Nile, but also modified the river by building dams and developing irrigation systems. The flow of the Nile then became more and more unnatural, and the water supply could not match the rising demand.

Treaties during the British Colonial Era

Alarmed by the finite Nile water supply, Egypt, Sudan, and Britain (then coloniser of Sudan) signed two treaties in 1929 and 1959, which stated an absolute control of the River by Egypt and Sudan with a 75/25 split (Kameri-Mbote, 2007). These treaties are evidently inequitable to the upstream countries in the watershed and would give Egypt a disproportionate amount of economic advantage, despite it being a downstream, non-contributing country (El-Fadel et al., 2003). The treaties particularly undermined Ethiopia's rights to the Blue Nile, a major tributary that carries 85% of the Nile's water and flows through Ethiopian sovereign land (Ottaway, 2020).

Post-colonial Era

Water demand is growing in every riparian state and the upstream countries are starting to act unilaterally, while the water-scarce Egypt and Sudan, which have relatively lower annual rainfall levels, are desperately holding onto the colonial remnants of the Nile basin. The concerns of the Egyptian government are not unreasonable: 95% of the country's population lives on the narrow strip of land along the Nile River, and sources 90% of its water supply from the river (Tobias et al., 2020). The modern development of Sudan follows a similar trajectory: its civilisation prospered thanks to the Nile River, and the population is still currently concentrated along the watershed. When the upstream countries began to build hydroelectric dams and extract water for consumptive uses, Egypt threatened legal actions and called for African Union and United Nations intervention to 'preserve' their historical 'rights' (Pearce, 2010).

But as Ethiopia centralised enough economic power and political will, they made a comeback with the biggest hydropower facility in the continent- the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). It is a symbol of its industrial ambitions and determination to break out of the historical cycle of poverty that was inflicted upon it during the colonial era (Ottaway, 2020). The Europeans' prolonged exploitation of lands, resources and labour force, along with the splintering of African society and values, have caused irreversible damage to the colonies. Any concession on the Ethiopian side would mean giving up on the already delayed economic development and yielding to the bilateral agreements from the colonial era.

The impacts of European invasion and intervention are still apparent until this very day, and have exacerbated the transboundary conflicts of the riparian states. The following few blogs will zoom into a case study of the aforementioned GERD and closely examine the post-colonial, rapidly changing power dynamics along the banks of the River Nile.

Comments

Post a Comment